The course of action being proposed in this rulemaking is illegal. We have said this repeatedly and without hesitation from the day Director Robbins introduced his so-called “15 objective criteria.” That was roughly a month ago. We say it again today, hoping someone on this new commission will take notice.

His criteria are hardly objective. They are in our judgment simply arbitrary and capricious.

The signal feature of Mr. Robbins “15 objective criteria” is a 1500-foot setback from homes in municipal settings. He is silent on what rural people deserve in terms of protection. Indeed the 1500 feet is not really a setback, but a threshold requiring further review by his office. Apparently, any drilling proposal that is greater than 1500 feet from an urban dwelling is deemed safe. These criteria are to rule oil and gas permitting procedures until real rules can be developed for SB 19-181. Mr. Robbins says this may take 2 years or more.

We invite your attention to the declaration of intent in SB 19-181, which became the law of this state two months ago on April 16. The legislature directed state government to “regulate the development of the natural resources of oil and gas in the state of Colorado in a manner that protects public health, safety, and welfare, including protection of the environment and wildlife resources;” p 9-10.

Mr. Robbins cannot demonstrate his 15 criteria comport with this foundational requirement of the law. Neither can he demonstrate his criteria are consistent with the state’s Administrative Procedure Act which says that for any rule to be valid it must not conflict with other provisions of the law. The conflicts are various and far reaching as we shall demonstrate.

In our judgment, the following are the subjects that must be addressed through rulemaking before new drilling and supporting infrastructure can be built. We have listed them in order of their importance–from our perspective. All of them are essential to understanding the impacts of oil and gas on the public’s welfare and the environment. All of them must be integrated into the regulations that guide the activities of the COGCC and the CDPHE. The CDPHE has essential and serious responsibilities under the new law. Director Ryan, it is our judgment these responsibilities have simply been ignored up to this point.

In order of their importance we list:

- Setbacks

- Cumulative impact analyzes

- Bonding

- Financial Assurance

We would remind you that though the legislature did not address climate collapse directly in this legislation, we believe it is implicit to the purposes of the law, since the public’s welfare cannot be protected unless we recognize climate protection as essential to our continued existence.

Setbacks

We’ll start off here with several photos of oil and gas explosions. They are intended to provide context for a discussion of setbacks.

Even a quick look will dispel any doubt that this is a feather floating across the landscape. No, it is a 20,000-gallon (estimated) frack waste storage tank exploding off its foundation. If filled with liquid it would weigh about the same as a small steam locomotive, about the size of the Hogwarts Express. All those present who would like to live within 1500 feet of such a floating behemoth please raise their hand.

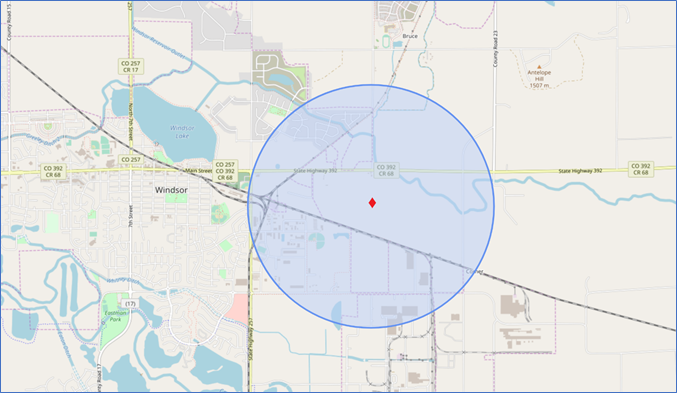

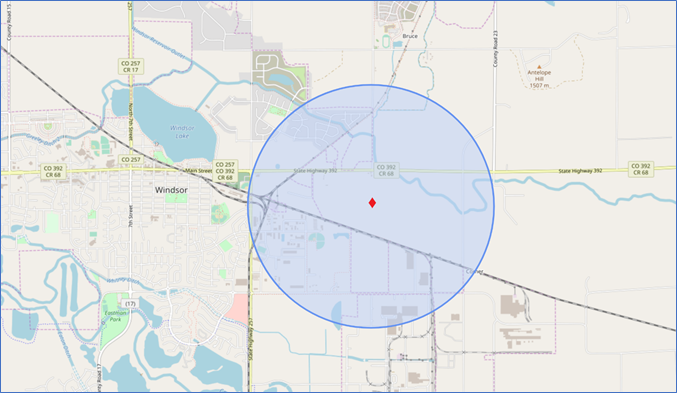

Windsor fire at an Extraction drill site northeast of the town

This photo is of the Windsor fire at an Extraction drill site northeast of the town. There was apparently an uncontrolled gas leak throughout the day. The gas finally ignited. A spike in benzene was measured in Boulder County, 40 miles away at the state’s only continuous air monitoring site. One can only imagine what the benzene concentrations were in and around Windsor. Benzene is a carcinogen. It is ubiquitous in oil and gas production. It is unsafe for humans at any concentration.

Reportedly, eight fire departments were involved in extinguishing the fire. The local fire marshal established a fire line or setback one-mile distant from the well site. The fire fighters used all the fire suppressing foam available in northern Colorado to extinguish the fire. This foam, called AFFF, is also a carcinogen responsible for large-scale ground water contamination in the United States. The groundwater contamination in Fountain, Colorado, is a close-to-home example.

This is a picture of another explosion at a drill site in Oklahoma. Five workers were killed, one a Coloradan. The fire was so intense that firefighters couldn’t get near enough to extinguish it for over a week. Here again the fire line was one mile.

Obviously 1500 feet is not supportable as protective of public health and safety. We are not suggesting attribution, but we do note that 1500 feet was a compromise position developed for the industry by RS Energy last year in the battle over Prop 112, which, as you know, called for a 2500-foot setback. At 1500 feet the impacts on the industry’s core holdings would be minimal according to the industry study. Even Extraction, whose business model is based on urban drilling, sometimes within shouting distance of little Dick and Jane’s swing set, would have been only moderately impacted.

Mr. Robbins may not have pulled his 1500-foot setback “criteria” from a hat. He may have devised it to minimize the impacts to the oil industry. But that is the wrong answer to the wrong question. The question is no longer how do we minimize regulatory impacts on oil and gas development in this state, but how do we protect the public? What setbacks are required to do that?

We don’t have a hard answer to this question. But statistical studies have been conducted by the Colorado School of Public Health (CSPH) which suggest 2500 feet may be a reasonable minimum. Researcher Lisa McKenzie and her colleagues at Anschutz state that air pollutants from oil and gas operations “are potentially a major health risk for nearby populations.” The study showed an increase in the incidence of cancers occurred within 2500 feet of these facilities. Other studies from Anschutz researchers show increased incidence of childhood leukemia in a residential setting up to a mile away from drill sites.

Governor Polis might have been right when he said one size does not fit all. In fact, it appears 2500 feet might be the reasonable and necessary minimum setback, but topography and prevailing wind patterns at a proposed oil facility could cause the safe setback to be lengthened dramatically using the precautionary principle as guide.

Remember it was Senator Foote, one of the sponsors of the SB 19-181, who emphasized on the floor of the senate that it was the precautionary principle that should guide decisions in this rulemaking. So, unless the industry clearly demonstrates public safety can be maintained at a distance less than 2500 feet, as a minimum, the science that exists must stand as guide.

Cumulative impacts

We note that the law, on p.19, directs the CDPHE to participate in developing these important data sets that are essential to health, safety, and environmental impact evaluations.

Water: The volume of fresh water needed for fracking is alarming. For example, if all of the roughly 6500 drilling permits received by the COGCC in 2018 were to be approved, and all were for horizontal wells, the total water demand might be about 65 billion gallons. That is more than the treated water than Denver Water supplies to its customers annually. It is in fact, over twice the amount since over half of the domestic water demand gets back into the hydrologic system to be used again and again downstream. From a cumulative impact standpoint, we should want to know how much water will be needed annually for fracking over the next 10 years, and whether that demand is sustainable. The base condition for this analysis should be the estimated amount of water the industry has used by year since 2008, the advent of the fracking invasion.

A recent study at Duke University shows that from “2011 to 2016, the water use per well increased up to 770%, while flowback and produced water volumes generated within the first year of production increased up to 1440%,” and this was across all regions. Their conclusion is that the volume of water and liquid toxic waste will only increase in the coming years. It’s time we started treating fracking’s cumulative impacts with the seriousness they deserve, and with the diligence the new law demands. The seat-of –the-pants approach, where we basically rely on the industry for all important information, must be abandoned.

With regard to the water sustainability issue, the impact of diminished surface supplies predicted from the climate crisis should also be examined using sensitivity analysis since we are unsure of the exact snowpack and runoff reductions we can expect from a hotter and drier climate in the southern Rockies.

This sort of analysis becomes even more important in light of the efforts to get the taxpayers to underwrite billions of dollars in new projects for water that is not likely to exist in the future with even moderate climate change. Some of this water, we read, is earmarked for fracking.

A thorough review of the Class II injection well process needs to be undertaken, as well. That injection process was implemented in the early 1980s and hasn’t undergone any serious review since, even though the original purpose of the program was to allow old played out vertical wells, designated Class II wells, to be reinjected with liquid waste from nearby producing wells to increase underground pressure and thereby stimulate production at the nearby producing well. It is now used to dispose of almost all liquid toxic waste from fracking activities.

Here again the baseline condition should be the amount of toxic liquids the industry has pumped annually into Class II wells since 2008. Using a 10 -year planning horizon, how much toxic liquid will be generated for disposal? Is the present Class II system adequate to handle this volume, or will new wells be required? We know that some Class II wells have been approved for injection into potable water supplies, primarily because those supplies were thought to be too far from demand to ever be tapped for domestic or industrial use. Given the realities of climate change should this program be terminated? From a sustained use standpoint, better tracking of the original estimated capacity of these Class II reservoirs, the approved injection rate, and remaining life expectancy need to be developed and analyzed for their cumulative effects. For example, how many new disposal wells might be needed under a range of reasonable projected disposal requirements? What are likely to be the local and regional impacts if new wells are required? Clearly, the list could go on, but this kind of data is necessary in any adequate cumulative impact evaluation on fresh water use and toxic liquid disposal.

AIR: A monitoring system that is continuous across the oil patch, upstream and midstream, is necessary. This technology exists and must be employed. Our air quality is so compromised, much of it from oil and gas activity, that nothing less is morally acceptable, and SB 19-181, to be effective, demands it.

Continuous system measurements must be immediately available to state and local governments, free of massage or filtering by the industry. In other words, it must be state run and verifiable by local and regional oversight. Recent articles in the Colorado Independent and the Denver Post simply underscore why such a system is nonnegotiable—public trust must be restored. A recent letter from WildEarth Guardians to Governor Polis, dated April 23, 2019, exposes the general lawlessness that exists within the state’s regulatory system, particularly with regard to the federal Clean Air Act. Specifically, the state has allowing the oil and gas industry to operate for 90 days or longer without the required clean air permits. As a result, VOCs and poisonous gasses such as benzene have been released without restriction or measurement.

VOCs are a major contributor to the northern Front Range’s ozone problem. Denver, as a result, has been judged to have the 12th worst air quality of any city in the country, sometimes beating out Beijing, China, for the honor of really bad. NOAA measurements indicate an estimated 55 percent of the VOCs, above background, come from fossil fuel operations in the Front Range, primarily Weld County.

Unfortunately, the monetary and social impacts of ozone pollution are mostly available only on a macro scale. The CDC, in 1980, well before the fracking invasion, estimated asthma, for which ozone pollution is a major cause, costs the U.S. economy about $80 billion annually in sickness and lost work. We are obviously more than paying our fair share.

A more recent study by the Office of Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) concludes premature deaths from ozone pollution have dramatically and continuously increased over the last decade and a half. Overall, they conclude that air pollution in 2015 was responsible for 3.2 million premature deaths globally and cost the world economy $5.1 trillion.

The World Health Organization has said air pollution is the “worlds single largest health risk.” This assessment excludes climate collapse, of course, for it is not just a health risk, but an existential risk. A few may perceive from this discussion that a rapid conversion to renewables and a quickening denial of all new fossil fuel development might save our bacon.

Given the above, and to be effective and have public acceptance, the monitoring system mandated by the law must incorporate the following:

- It must be continuous and independent of industry manipulation.

- It must be verifiable to preclude tampering.

- It must delineate the various chemicals being released. This capability is essential from a health perspective, for one cannot simultaneously measure the human health effects of oil development’s point source methane (a nontoxic) and benzene (a proximate toxic) contributions with the same probe.

- Those who talk of VOCs will be looking mainly to the longer term human effects of ozone, thus to dispersing, aging plumes. Such plume emphasis will neglect the proximate toxicity of point sources of benzene because its concentrations cannot be accurately captured by plume sampling, continuous or otherwise. To accurately assess the overall health effects of oil production‘s point source pollutions, two separate probing techniques will be necessary—one for ozone and one for proximate benzene exposures as their atmospheric behaviors are significantly different.

- It should be compatible and useful to recent legislation dealing with better measurement of green house gas emissions, and the move toward renewables. See SB 19-096 and HB 19-1261. While 1261 establishes the goal of achieving 90 percent reduction in green house gasses from all sources by 2050, bill 096 seeks the collection of better data on green house gas emissions. Both should be integrated into this monitoring system as a guard against redundancy and bureaucratic jealousies. We should note here that HB 1261 is directed to our use of fossil fuels, not the industry’s development of them. Most the product, both oil an gas, is shipped out of state, but many of the major impacts stay here. Colorado has become an oil colony, much like Nigeria.

LAND: The law, in our judgment, now requires, as with air and water, cumulative impacts on land use be calculated with each new oil and gas development and that the result become part of the public record. We suggest that the oil and gas land-use base include and identify each industry use category: well pads, storage and operational facilities, pipelines by class–including federally monitored interstate pipelines, underground storage reservoirs. compressor stations, access roads, disposal and waste injection facilities, etc. We think it advisable that the land use impacts be delineated and identified by their ownership class: public, private, etc.

Wildlife impacts from oil and gas land use requirements greatly concern us. How could they not, since scientists tell us “the Earth is in the midst of a mass extinction.” They tell us that up to 200 species of plants, animals , insects, and birds go extinct every day. This is unlike anything since the dinosaurs disappeared 65 million years ago. We suspect fossil fuel development plays a significant part in this die off. In fact, land use changes from fracking certainly have a greater impact on deer populations than does bear and cougar predation. The state recently floated the idea of killing bear and cougar so that more deer could be killed by hunters. We suggest that killing off a few old wells every year accompanied by land use restoration would be more beneficial to both deer and humans. The beer and cougar would cheer, too.

One of our greatest public health concerns under the land use category is radioactive frack waste disposal. Measurements of these wastes must conform to scientifically acceptable protocols. The EPA 900 series, currently in use, fails this test. It underestimates radioactive levels by at least a factor of 100 (and in cases of scale and sludge by as much as 1000 or even 10,000 times).

For example, accurate radiation measurements of frack-waste require an expensive, in-laboratory spectrometry device and at least a 21-day holding period (to account for daughter radiation). This requirement is currently being bypassed. For example, a simple Geiger counter assessment typically misreads the radiation present, allowing dangerously radioactive waste to be released into ordinary land fills, or worse on area roads as a dust suppressant.

The cost of this independent, third-party, safety measurement of radiation should be borne by the Operator, as should all regulatory costs created by industry activity. Such an approach is consistent with the expectations as set forth in SB 19-181.

BONDING

SB 19-181 directs the COGCC to revisit the bonding requirements to determine what bonding is needed to adequately protect the public from someday inheriting the costs of closing and maintaining the industry’s old, played-out wells.

Last year about $5 million was allocated from the state’s general fund to close a few old, abandoned wells the COGCC had determined were an immediate health and safety risk. The cost came to about $250,000 per well. The COGCC has identified 365 abandoned wells that should be soon closed for public health and safety reasons. The legislature will have to allocate at least $91 million from the general fund to close them, and that’s only if there are no surprises. In California, the cost of closing two old wells in Hollywood ran to about a $1 million each. It is almost axiomatic that the closer fracked wells are to people and important public resources such as water courses, the greater the costs of closing and monitoring.

Recently, a leaked government report from the Canadian province of Alberta set the likely cost of closing all old wells and other infrastructure in the province at $130 billion, with another $130 billion needed to close and restore the province’s tar sands operations. This $260 billion price tag was vastly different from the government’s “public” story which claimed that all the restoration could be done for $50 billion. The province has less than $1 billion in a trust fund for environmental restoration. Colorado as we’ve just related, has none. And Colorado has about half of Alberta’s 200,000 wells.

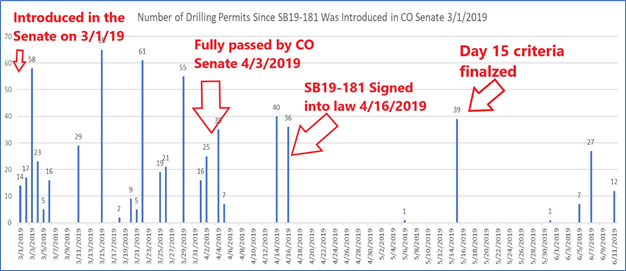

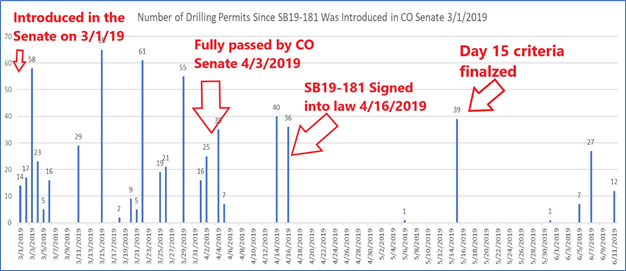

As we looked at the number and timing of drilling permits the COGCC was approving this year, our reaction was four alarm. For example, one can see from the following chart that immediately prior to the governor signing SB 181 into law on the 16th of April, there was frenzied activity to get almost 80 drilling permits out the door, some only minutes before Governor Polis signed the bill. These were mostly rural permits, many in Weld County.

Wells approved:

Since January 1, 2019 – 1199

Since March 1, 2019 – 633

Since SB181 Signed – 87

Day 15 criteria finalized – 39

graph by Maira Orms, Be the Change

The Polis administration undoubtedly wanted to avoid delays the new law mandated, such as setback determinations to protect health and safety, continuous air monitoring, etc. And mostly of course the governor probably wanted to keep Weld County commissioner Barbara Kirkmeyer and her four sidekicks from riding into town on their snorting steeds to properly frighten us latte-swilling city slickers and remind us that their ozone laden air was a necessary burden from Weld so that the county’s operating budget, which is dependent on the industry’s property tax payments, could survive and flourish—at least until we achieve the looming climate collapse.

But in this rush to demonstrate that all setbacks are not the same, as the governor often declares, the new administration also provided a hidden subsidy to the industry in just a couple of days of at least $20 million, for that is the difference between what the industry would have had to pay if bonding had been increased to reflect actual costs and what they pay now—a maximum of $100,000 for all wells.

Similarly, on the day Mr. Robbins finalized his “15 objective criteria” his office approved 39 new drilling permits. His criteria are silent on bonding. Thereby, Mr. Robbins handed the industry a $10 million subsidy on that day alone.

The following chart shows that this administration has been working overtime to get drilling permits out the door. In fact, with about 1200 permits approved since the first of the year– This is a pace that far exceeds that of the Hickenlooper administration. Hickenlooper of course insists to this day that fracking is safe. We can only conclude that SB 19-181 hasn’t changed much of anything in the fracking world, and will not until this administration enforces the law so as to protect the public and the planet. The bonding subsidy from 1200 permits is roughly $300 million.

Clearly, adequate bonding is a very real public welfare issue, one the new law directed the COGCC to examine through rulemaking. The COGCC has failed out of ignorance and its desire, perhaps, to protect the interests of the industry over those of the people. Our suggestions are as follows:

- The minimum bonding requirement for any well must be $350,000. This estimate is based on the actual cost of closing a few orphaned wells at public expense in the past year. As we’ve said, each of these wells cost about $250,000 to close. But since old wells have to be monitored and rehabbed over time—steel corrodes and cement breakdowns—we suggest the addition of $100,000 as a hedge against future maintenance costs.

- If wells, old or new, threaten public health or the environment by their proximity to people, dedicated open space, or water resources, the costs could be upwards of $1,000,000. Actual well closings in California and Alberta have reached these cost levels. Bonding should reflect these realities. This means that bonding close to people and their resources will cost substantially more, and should.

- Any approval for sale or transfer of wells must be conditioned on the new owner assuming the bonding requirements outlined above. Mandatory new bonding is an extremely important concept because in our opinion, and that of many financial analysts, the industry is hopelessly in debt, and likely to never recover.

- We think the bonding should be a cash bond held in trust by the state

- The state needs to follow Alberta’s example and determine the public’s likely liability associated with well closing and maintenance. California, aware of the longterm fiscal threat old wells represent, passed a billthis year to assess the costs of oil and gas cleanup. We recommend that any cleanup cost study be conducted by an independent or academic institution.

- The quickest way to generate revenue for long-term care and closing of old wells is to increase the severance tax and establish a dedicated trust fund with the revenues. Colorado’s severance tax rate is now has an effective .7 to .9 percent. This is so because drillers get to deduct the property taxes they pay counties such as Weld from their severance tax obligation to the state. The result is that in many years the oil industry in counties such as Weld pay no severance tax to the state. In 2016 Weld collected $490 million in property taxes from the industry. The state had to take roughly $13 million out of the general fund to keep the doors at the COGCC open. Whatever the increased severance rate, it must be adequate to start covering the long term estimated closing and maintenance costs of wells in the oil fields, especially those of Weld County.

FINANCIAL ASSURANCE

The law now requires “that every operator… provide assurance that it is financially capable of fulfilling EVERY obligation imposed” by the new law, p. 19. And that the “operator demonstrate sufficient net worth to guarantee performance, and that the commission annually review the guarantee and demonstration of net worth.” p. 20.

These requirements, like the other we’ve outlined above, are in full force and effect, but like the others, the Polis administration has sidestepped them for reasons we can only guess at.

Had they not evaded these requirements of the new law, they would have learned the fracking industry is close to financial collapse. It has lived from the day of conception on borrowed money from Wall Street and hedge funders. Wall Street is now turning away. Monetary institutions and insurance companies are increasingly leery of fracking as an investment. The industry’s assets, their fossil fuel reserves, will be worthless if the leave-it-in-the- ground and international kids movements are eventually successful, as they must be if we are to avoid destroying our kind through ignorance, corruption, and greed.

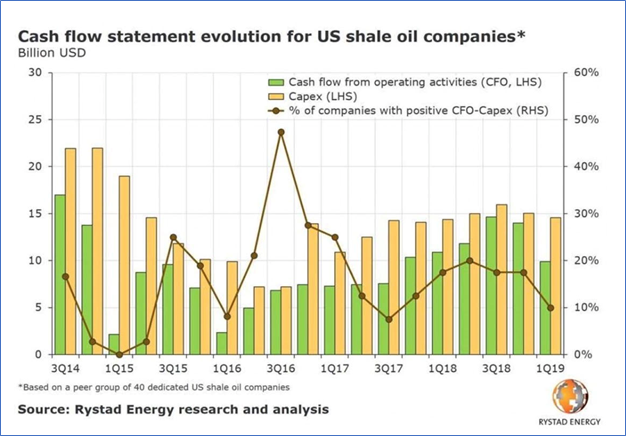

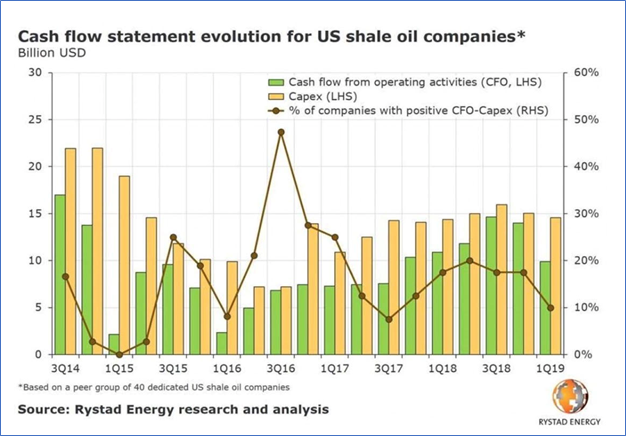

The following graph shows that, even with Trump’s corporate tax cuts, the fracking industry can’t show a profit.

Their operating costs inevitably exceed their revenues. As a result “174 North American oil and gas producers have filed for bankruptcy protection, restructuring nearly $100 billion in debt, largely through write-offs,” since 2015. One analyst, as reported by Bethany McLean in her recent bookSaudi America, has remarked that, “The real catalyst for the shale revolution was …the 2008 financial crisis and the era of unprecedented low interest rates it ushered in.”

In Colorado the largest driller, Anadarko, has amassed, according SEC filings, over $19 billion in debt. The new urban fracker, Extraction Oil and Gas, after only a few years of operation, has managed to amass over $1.5 billion in debt. Overall, the frackers in the United States are at least $220 billion in debt.

SUMMARY: It is our judgment that there is no grace period for the oil and gas industry or the Polis administration to adjust to the new law. SB 19-181 changed the way the industry is regulated, and those changes became law on the day the governor signed the bill. If government changes the speed limit from 60 mph to 25 mph, on a section of road because of health and safety concerns, drivers do not get a grace period to adjust. The same should be true of the oil industry. This will cause delays in approving permits, but the delays are necessary to satisfy the law and protect the people. For too long the industry has had the run of the state. A significant law was passed to make citizen health, safety, and welfare, and the protection of the environment and wildlife a condition for continued oil and gas development in this state. As a result new life was breathed into our state constitution’s Bill of Rights which posits:

All persons have certain natural, essential and inalienable rights, among which may be reckoned the right of enjoying and defending their lives and liberties; of acquiring, possessing and protecting property; and of seeking and obtaining their safety and happiness. Art II, Sec 3, Colorado Constitution.